Understanding Automatisation in the Age of Intelligent Machines

Automatisation is the process of using technology—from mechanical devices to artificial intelligence—to perform tasks with minimal human intervention. It aims to increase efficiency, reduce errors, and enable operations that would be impractical for humans alone, fundamentally changing how we work, produce goods, and deliver services.

Quick Overview: What You Need to Know

- Definition: Automatisation uses machines, software, and AI to execute tasks previously done by humans, often with greater speed, consistency, and scale.

- Key Difference: While « automation » typically refers to mechanical task execution, « automatisation » encompasses intelligent, adaptive systems that can learn and adjust.

- Impact Scale: 47% of US jobs could be fully automated by 2033, with 192 million workers globally potentially affected.

- Core Benefits: Higher productivity, improved quality, improved safety, 24/7 operation, and reduced costs.

- Major Challenges: Job displacement, high upfront investment, skill gaps, and ethical concerns around bias and accountability.

The term « automation » wasn’t widely used before 1947, when Ford established its automation department. Yet the concept stretches back centuries—from ancient water clocks to the Jacquard loom’s punch-card programming in the early 1800s. What’s changed dramatically is the intelligence behind these systems.

Today’s automatisation isn’t just about replacing manual labor. It’s about creating adaptive systems powered by AI and machine learning that can make decisions and optimize processes in real-time. A modern automated factory doesn’t just run conveyor belts—it uses sensors and data analytics to adjust production dynamically based on demand and quality metrics.

This shift is crucial for business leaders. Automatisation directly impacts customer interactions through tools like self-checkout systems, chatbots, and personalized recommendations. These are not just operational tools; they are touchpoints that shape the customer experience. Understanding automatisation helps leverage these technologies strategically while maintaining the human connection that drives engagement.

The implications extend beyond business operations. Between 3 and 14 percent of the global workforce may need to switch job categories entirely by 2030 due to automation. This creates both an opportunity to build more efficient businesses and a responsibility to consider the human impact of technology.

This guide explores what automatisation means, its evolution, benefits, limitations, and societal impact. You’ll gain practical insights into the technologies reshaping our economy, grounded in real-world examples.

What is Automatisation? Core Concepts and Key Distinctions

At its heart, automatisation refers to the strategic and technical implementation of systems that operate with reduced human intervention. It’s a broad concept, but its meaning can shift depending on the context.

Defining Automatisation Across Different Fields

Let’s explore its meaning across various domains:

-

Industrial Context: In the industrial sector, automatisation uses machinery and control systems to perform tasks previously done by human labor, from assembly line robots to process controls in chemical plants. The primary goals are to increase production speed, maintain consistency, and ensure safety.

-

Technological Systems: From a technological standpoint, automatisation is about leveraging software and hardware to create self-operating systems. This includes IT automation, where repeatable tasks like configuration management, deployment, and security are performed with minimal human input, providing a key competitive advantage.

-

Psychological Processes: In psychology and linguistics, « automatisation » refers to a skill becoming automatic through repetition, requiring little conscious effort. Think of learning to drive a car; initially deliberate, the actions eventually become « automatized, » transitioning from conscious effort to unconscious competence.

-

Business Process Automation (BPA): Within business, BPA uses technology to streamline complex processes. It can involve integrating applications and deploying software to improve service quality, improve delivery, and contain costs, making operations simpler and more efficient.

Across all these contexts, the common thread is the reduction of human intervention.

Automatisation vs. Automation: Why the Difference Matters

Though often used interchangeably, « automatisation » and « automation » have distinct meanings, particularly in the tech world. Understanding this nuance is important for strategic planning.

Generally, « automation » refers to a broad strategic framework of intelligent, adaptive systems designed to reduce manual effort across an entire workflow. In contrast, « automatisation » is narrower, often describing the process of making a single, repetitive manual task automatic. The Collins English Dictionary defines « automatisation » as « the process of making something automatic or self-regulating. »

Here’s a comparison to illustrate the key distinctions:

| Feature | Automatisation | Automation |

|---|---|---|

| Scope of Tasks | Narrower; focuses on making specific, often repetitive, tasks automatic. | Broader; encompasses strategic frameworks for reducing manual effort across systems. |

| Level of Intelligence | Can be rule-based or involve simpler machine processes. | Often involves advanced AI, machine learning, and adaptive intelligence. |

| Decision-Making | Predetermined or simple decision rules for a specific task. | Adaptive, context-aware decision-making, learning from data and optimizing. |

| Human Involvement | Reduces human effort for a single task; can be about replacing a specific action. | Aims to augment human capabilities, freeing up humans for higher-value work. |

| System Adaptability | Less adaptive; typically follows predefined steps. | Highly adaptive; capable of learning, adjusting, and optimizing in real-time. |

As the Beam AI article « Automation vs. Automatization » explains, the choice of terminology influences how organizations approach technology. Using « automation » conveys a forward-looking strategy that scales innovation, while « automatisation » can imply more incremental, task-specific changes. Misunderstanding these terms can hinder effective digital change.

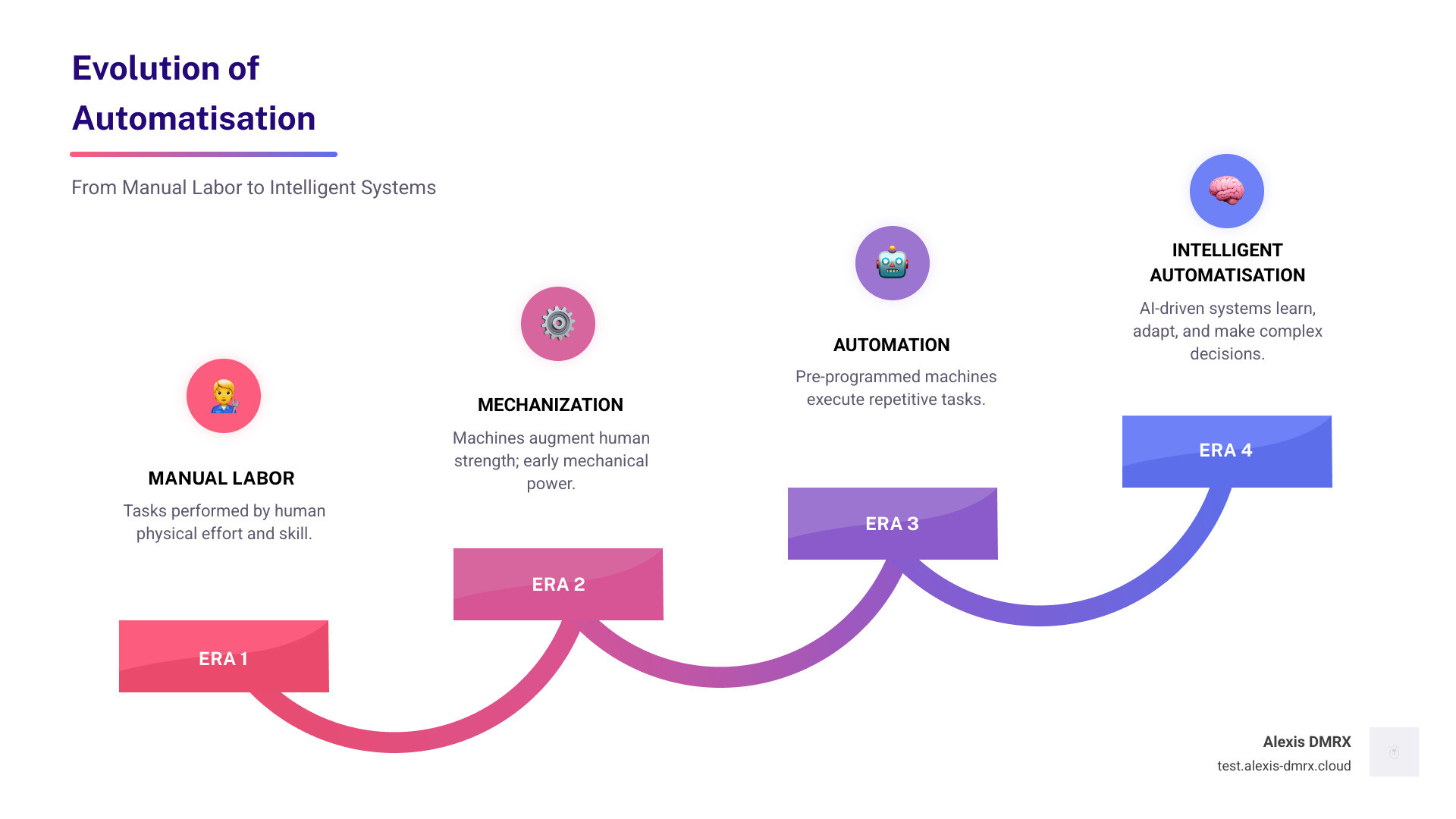

The Historical Journey of Automated Systems

The story of automatisation is a centuries-old quest to create machines that perform tasks independently, reflecting humanity’s enduring ingenuity.

The quest for self-operating devices is ancient. Early examples of feedback control include Ctesibius’s water clock (3rd century BC) and the automatic controls described by the Banū Mūsā brothers in the 9th century. The mechanical clock in the 14th century and the centrifugal governor in the 17th century marked further significant leaps in mechanical autonomy.

However, the true acceleration of automatisation began with the Industrial Revolution. The steam engine’s arrival in the 18th century created a need for automatic control systems, such as James Watt’s centrifugal governor. This era also saw the birth of programmable machines. The Jacquard loom, devised around 1801, was a pivotal invention that used punch cards to control intricate textile patterns, automating a highly skilled manual process and serving as a direct precursor to modern computer programming.

Other milestones included Richard Arkwright’s automated spinning mill (1771) and Oliver Evans’s automatic flour mill (1785), the first completely automated industrial process. The 20th century brought the « Space/Computer Age » of automatisation. Factory electrification and relay logic led to central control rooms, and by 1929, nearly a third of the Bell telephone system was automatic.

A striking example of early industrial automatisation is the first commercially successful glass bottle-blowing machine from 1905. This machine produced 17,280 bottles in 24 hours, while a six-person crew made only 2,880. The cost plummeted from $1.80 per gross by hand to just 10 to 12 cents per gross by machine, illustrating the transformative power of automatisation.

The mid-20th century introduced Numerical Control (NC) for machine tools, and Ford coined the term « automation » in 1947. The development of solid-state electronics led to Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs), which revolutionized industrial control. These specialized computers replaced complex relay logic, offering new flexibility. Today, automatisation is ubiquitous in manufacturing, with the number of industrial robots soaring from 700,000 in 1997 to 1.8 million in 2017.

The Benefits and Drawbacks of Widespread Automatisation

The pervasive nature of automatisation brings both significant advancements and complex challenges.

Primary Advantages Across Industries

The implementation of automatisation brings a host of benefits driving its adoption:

-

Increased Productivity: Automated systems can operate 24/7 without fatigue, drastically boosting output. The 1905 bottle-blowing machine, for example, outproduced manual labor sixfold.

-

Improved Product Quality and Consistency: Automated systems perform tasks with less variability than humans, resulting in higher quality, greater accuracy, and less waste.

-

Improved Worker Safety: Automatisation removes workers from hazardous or repetitive environments, a key advantage in industries dealing with dangerous chemicals, extreme temperatures, or heavy machinery.

-

Reduced Operational Costs: While initial investment is high, automatisation leads to long-term savings in labor, materials, and energy. The cost of bottle production, for instance, dropped from $1.80 per gross by hand to just 10-12 cents by machine.

-

Performing Tasks Beyond Human Capability: Automated systems can execute tasks that are too fast, precise, heavy, or tedious for humans, such as micro-assembly or processing vast amounts of data.

Significant Disadvantages and Limitations

Despite its advantages, automatisation has downsides that warrant careful consideration:

-

High Initial Capital Investment: Automated systems can cost millions, creating a significant barrier to entry for smaller businesses.

-

Potential for Job Displacement: This is a major concern. Studies suggest 47% of US jobs could be automated by 2033, and up to 14% of the global workforce may need to switch job categories by 2030. The introduction of industrial robots has already been shown to reduce employment.

-

Loss of Manual Skills and Human Adaptiveness: Over-reliance on automated systems can lead to the degradation of manual skills. Furthermore, human adaptiveness in handling unforeseen problems is difficult to replicate in machines.

-

System Complexity and Maintenance: Highly automated systems are complex and require specialized knowledge for maintenance. Malfunctions can be extremely costly, especially in high-volume production.

-

The Ironies of Automation: As described by Lisanne Bainbridge, a critical paradox exists: the more reliable an automated system, the more crucial the human operator becomes during a rare failure. This paradox of automation can lead to decreased vigilance but increased pressure in an emergency, shifting human error to a higher-stakes context.

-

Limitations of Current Technology: Despite advances in AI, tasks requiring nuanced judgment, empathy, or complex pattern recognition remain beyond the capabilities of modern systems and still require human expertise.

The Societal Impact: Employment, Ethics, and the Future of Work

The rise of automatisation is a profound societal change, redefining the relationship between humans and work and raising critical ethical questions.

The Impact of Automatisation on the Workforce

The most debated impact of automatisation is on employment. The statistics are startling:

- An estimated 47% of all current jobs in the US have the potential to be fully automated by 2033.

- A 2020 study in the Journal of Political Economy found that « One more robot per thousand workers reduces the employment-to-population ratio by 0.2 percentage points and wages by 0.42%. »

- Further research has shown that the introduction of industrial robots between 1993 and 2014 reduced employment for both men and women.

- Globally, 3 to 14 percent of the workforce may be forced to switch job categories by 2030.

However, while some jobs are displaced, automatisation also creates new roles, often in technology. The World Bank’s 2019 report, « The Changing Nature of Work, » suggests that new tech jobs may eventually outweigh the effects of displacement.

This shift necessitates significant reskilling. As Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee argue, « there’s never been a better time to be a worker with special skills… However, there’s never been a worse time to be a worker with only ‘ordinary’ skills. » This highlights the growing gap between those who can leverage technology and those whose routine tasks are easily automatized. Automatisation also has the potential to augment human capabilities, freeing us from repetitive and hazardous labor to focus on more creative and strategic tasks.

Ethical Considerations and Societal Challenges

Widespread automatisation introduces complex ethical challenges:

-

Economic Inequality: By favoring high-skilled workers and displacing others, automatisation could worsen economic inequality and social tensions.

-

Algorithmic Bias: AI systems trained on biased data can perpetuate and amplify discrimination in areas like hiring, raising serious questions of fairness.

-

Data Privacy Concerns: The vast data collection required for automated systems creates significant concerns about how personal information is used, stored, and protected.

-

Accountability in Automated Decisions: When an autonomous system errs—like a self-driving car causing an accident—determining legal and ethical responsibility is complex.

-

The Debate on Universal Basic Income (UBI): In response to potential job displacement, Universal Basic Income (UBI) has been proposed as a safety net to ensure a basic standard of living.

-

Political and Social Unrest: Job losses attributed to automatisation have been cited as a factor in the rise of populist and protectionist politics, highlighting the need for proactive social policies.

Technologies and Applications Shaping Our World

The current wave of automatisation is driven by a convergence of powerful technologies, leading to sophisticated systems that can learn, adapt, and make decisions across every industry.

Key Technologies Driving Modern Automatisation

The bedrock of modern automatisation lies in several interconnected advancements:

-

Artificial Intelligence (AI): AI provides the cognitive functions—like problem-solving and learning—that enable intelligent automatisation.

-

Machine Learning (ML): A subset of AI, ML allows systems to learn from data and improve over time, enabling predictive and adaptive operations.

-

Internet of Things (IoT): IoT networks of sensor-embedded objects provide the real-time data that intelligent systems use to monitor and control processes, forming the backbone of the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT).

-

Robotic Process Automation (RPA): RPA uses software « bots » to automate repetitive, rule-based digital tasks by mimicking human interaction with computer systems.

-

Cognitive Automation: This AI subset automates knowledge-based tasks that require human judgment, using technologies like natural language processing (NLP) to structure and interpret complex data at scale.

These technologies often work in concert, creating powerful, integrated solutions.

Real-World Applications and Case Studies

The applications of automatisation are vast and continually expanding:

-

Manufacturing: This is a leading sector for automatisation, with industrial robots handling assembly, welding, and quality control. The number of industrial robots in use reached 1.8 million by 2017.

-

Agriculture: « Agriculture 4.0 » uses automated machinery, robotic milking systems, and precision farming with drones and sensors to improve efficiency and reduce drudgery.

-

Logistics: Automated warehouses use robots and automated guided vehicles (AGVs) to sort, store, and retrieve packages, dramatically increasing supply chain speed.

-

Retail: Automatisation is reshaping retail through self-checkout systems, automated ordering, and the fundamental processes of e-commerce.

-

Construction: Automatisation in construction, including robotic bricklayers and autonomous excavators, aims to improve safety, speed, and quality control.

-

Mining: Automated mining uses autonomous drills and trucks to remove human labor from hazardous processes, improving safety and efficiency.

-

Video Surveillance: Automated surveillance systems monitor public spaces in real-time, generating alerts to improve security.

-

Highway Systems: Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) and self-driving cars aim to increase traffic capacity and reduce driver error.

-

Business Process: Business Process Automation (BPA) and Robotic Process Automation (RPA) are used to streamline workflows in marketing, sales, and administration.

-

Home Automation: Also known as domotics, this field automates household appliances for convenience and energy efficiency.

-

Laboratory Automation: Automated systems are widely used in labs to handle samples and perform tests, improving reproducibility, though high costs can be a barrier.

Conclusion: Navigating the Automated Future

Automatisation is a powerful force with a long history, now driven by AI and intelligent systems. While it offers clear advantages in productivity, quality, and safety, it also presents significant challenges. These include high initial costs, widespread job displacement, and the complexities highlighted by the « ironies of automation, » where the human role becomes more critical during system failures.

The societal implications are profound, demanding workforce reskilling and raising ethical questions about inequality, bias, privacy, and accountability. These are human challenges that require thoughtful solutions.

Looking ahead, AI, Machine Learning, and IoT will continue to drive automatisation. Cognitive automation and advanced robotics will keep pushing boundaries across all industries.

Navigating this future requires a balanced, human-centric approach to automatisation. We must ensure technology serves humanity by fostering continuous learning, designing ethical AI, and understanding human-machine interaction to build resilient systems.

At Alexis DMRX, we believe human perception remains paramount. Our neuromarketing focus helps businesses understand the psychological drivers of consumer behavior, allowing for deeper connections even as automated systems handle marketing mechanics.

The key is not just what we automate, but how we integrate these tools with human intelligence and values. By embracing ethical design and a deep understanding of human needs, we can open up the potential of automatisation for a more prosperous future.

To learn more about how human psychology intersects with advanced technologies, explore our insights on Neuromarketing Demystified: Understanding Consumer Neuroscience and Mind Games Market Gains: Unlocking Neuromarketing’s Secrets. For broader discussions on scientific advancements, visit our Science section.